Biologic

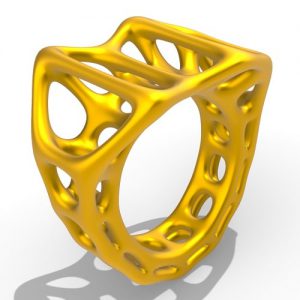

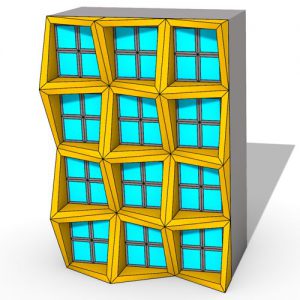

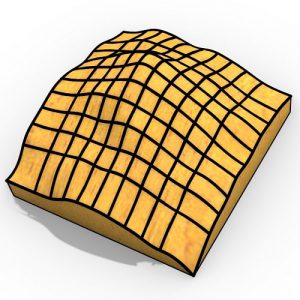

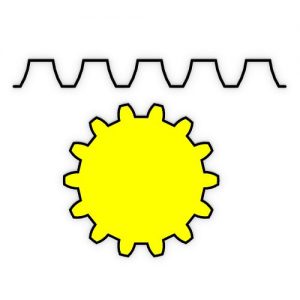

A team of MIT researchers has designed a breathable workout suit with ventilating flaps that open and close in response to an athlete’s body heat and sweat. These flaps, which range from thumbnail- to finger-sized, are lined with live microbial cells that shrink and expand in response to changes in humidity. The cells act as tiny sensors and actuators, driving the flaps to open when an athlete works up a sweat, and pulling them closed when the body has cooled off.

Why use live cells in responsive fabrics? The researchers say that moisture-sensitive cells require no additional elements to sense and respond to humidity. The microbial cells they have used are also proven to be safe to touch and even consume. What’s more, with new genetic engineering tools available today, cells can be prepared quickly and in vast quantities, to express multiple functionalities in addition to moisture response. To demonstrate this last point, the researchers engineered moisture-sensitive cells to not only pull flaps open but also light up in response to humid conditions.

“We can combine our cells with genetic tools to introduce other functionalities into these living cells,” says Wen Wang, the paper’s lead author and a former research scientist in MIT’s Media Lab and Department of Chemical Engineering. “We use fluorescence as an example, and this can let people know you are running in the dark. In the future we can combine odor-releasing functionalities through genetic engineering. So maybe after going to the gym, the shirt can release a nice-smelling odor.”

Wang’s co-authors include 14 researchers from MIT, specializing in fields including mechanical engineering, chemical engineering, architecture, biological engineering, and fashion design, as well as researchers from New Balance Athletics. Wang co-led the project, dubbed bioLogic, with former graduate student Lining Yao as part of MIT’s Tangible Media group, led by Hiroshi Ishii, the Jerome B. Wiesner Professor of Media Arts and Sciences.

In nature, biologists have observed that living things and their components, from pine cone scales to microbial cells and even specific proteins, can change their structures or volumes when there is a change in humidity. The MIT team hypothesized that natural shape-shifters such as yeast, bacteria, and other microbial cells might be used as building blocks to construct moisture-responsive fabrics.

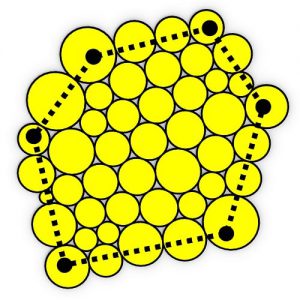

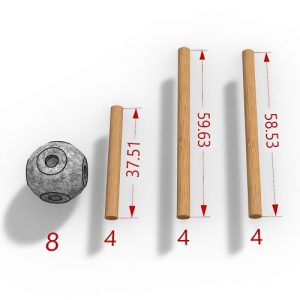

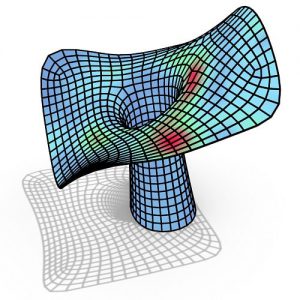

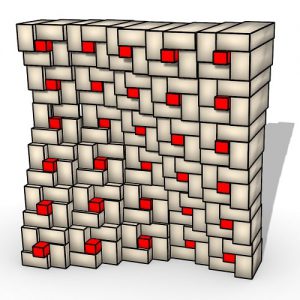

The researchers first worked with the most common nonpathogenic strain of E. coli, which was found to swell and shrink in response to changing humidity. They further engineered the cells to express green fluorescent protein, enabling the cell to glow when it senses humid conditions. They then used a cell-printing method they had previously developed to print E. coli onto sheets of rough, natural latex.

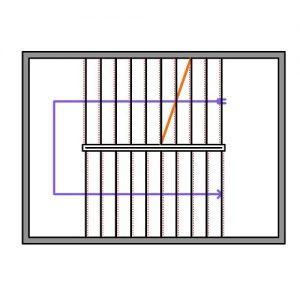

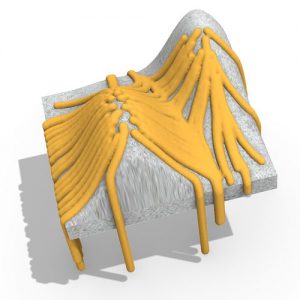

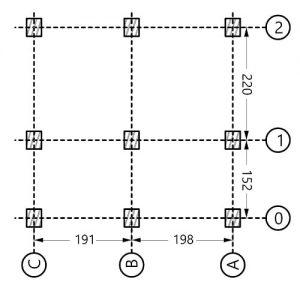

The team printed parallel lines of E. coli cells onto sheets of latex, creating two-layer structures, and exposed the fabric to changing moisture conditions. When the fabric was placed on a hot plate to dry, the cells began to shrink, causing the overlying latex layer to curl up. When the fabric was then exposed to steam, the cells began to glow and expand, causing the latex flatten out. After undergoing 100 such dry/wet cycles, Wang says the fabric experienced “no dramatic degradation” in either its cell layer or its overall performance.

Comments