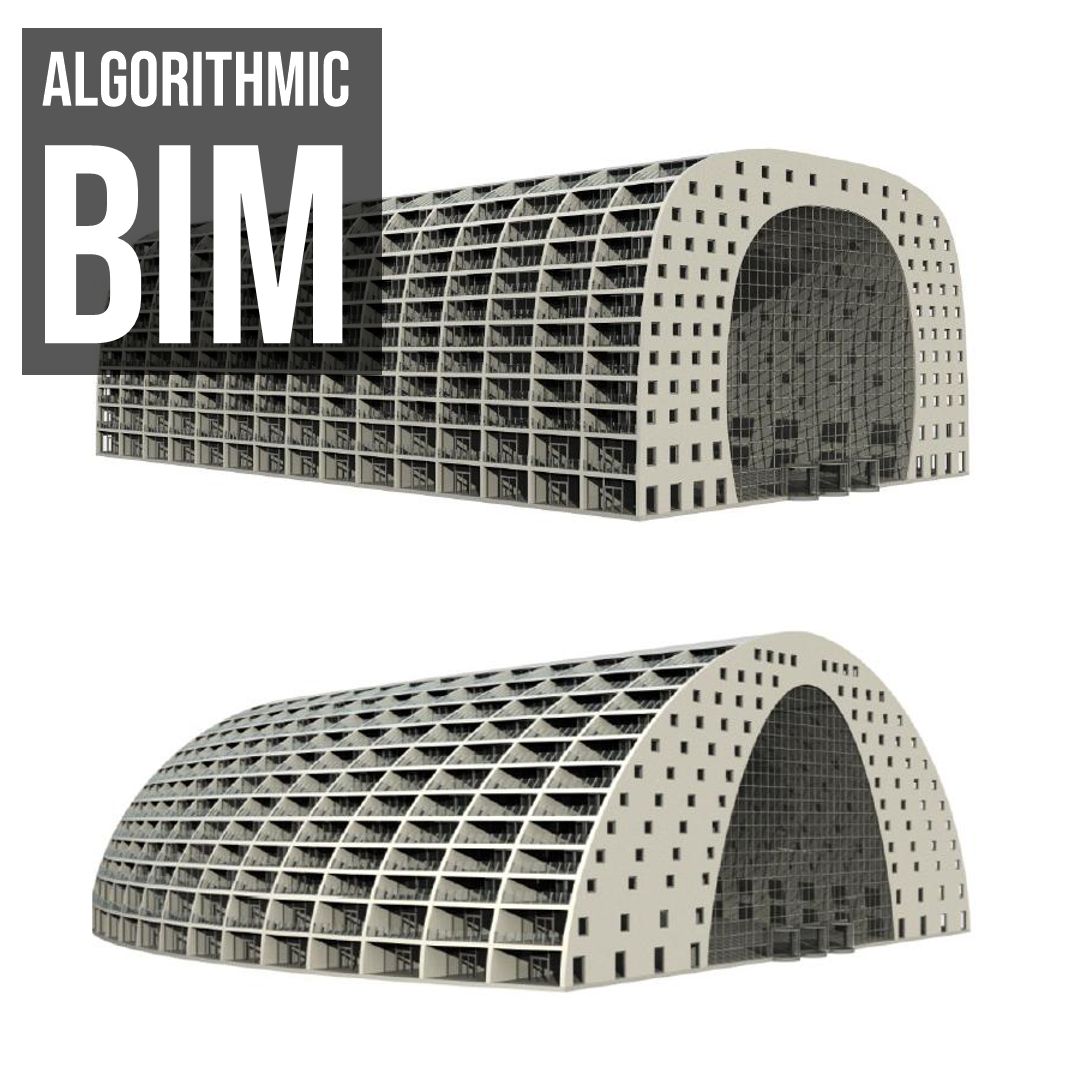

Algorithmic-based Building Information Modelling

A-BIM: Algorithmic-based Building Information Modelling

By: Sofia Teixeira de Vasconcelos Feist

May 2016

Along with the proliferation of affordable personal computers in the 1970s, a generation of Computer-Aided Design (CAD) systems became available to most architectural offices, consisting mainly of geometry-based drafting and modeling systems. Drafting systems in particular – in combination with improvements in communication and sharing among members of the design team brought about by the internet – improved the production of drawings in architecture and, consequently, the efficiency of the design activity which, nowadays, relies heavily on drawing documentation (Kalay, 2004).

Along with the proliferation of affordable personal computers in the 1970s, a generation of Computer-Aided Design (CAD) systems became available to most architectural offices, consisting mainly of geometry-based drafting and modeling systems. Drafting systems in particular – in combination with improvements in communication and sharing among members of the design team brought about by the internet – improved the production of drawings in architecture and, consequently, the efficiency of the design activity which, nowadays, relies heavily on drawing documentation (Kalay, 2004).

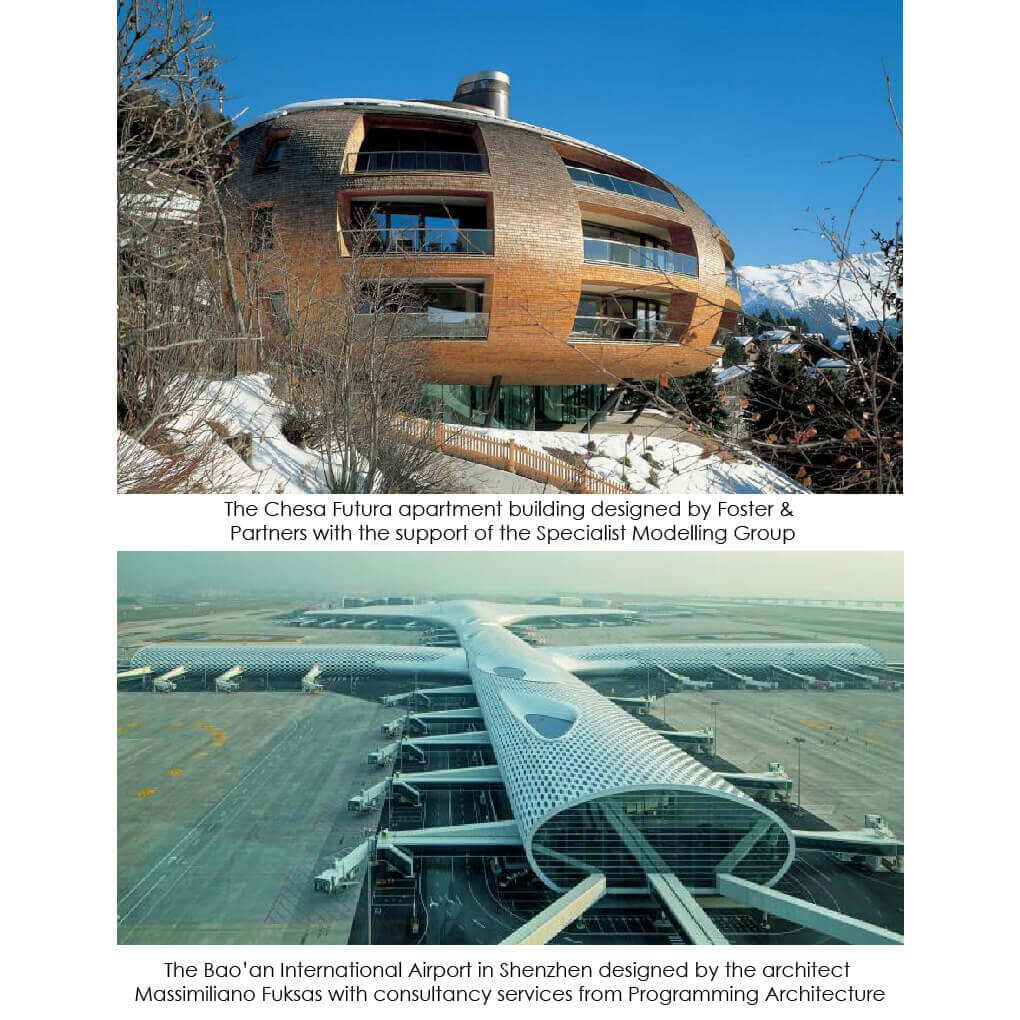

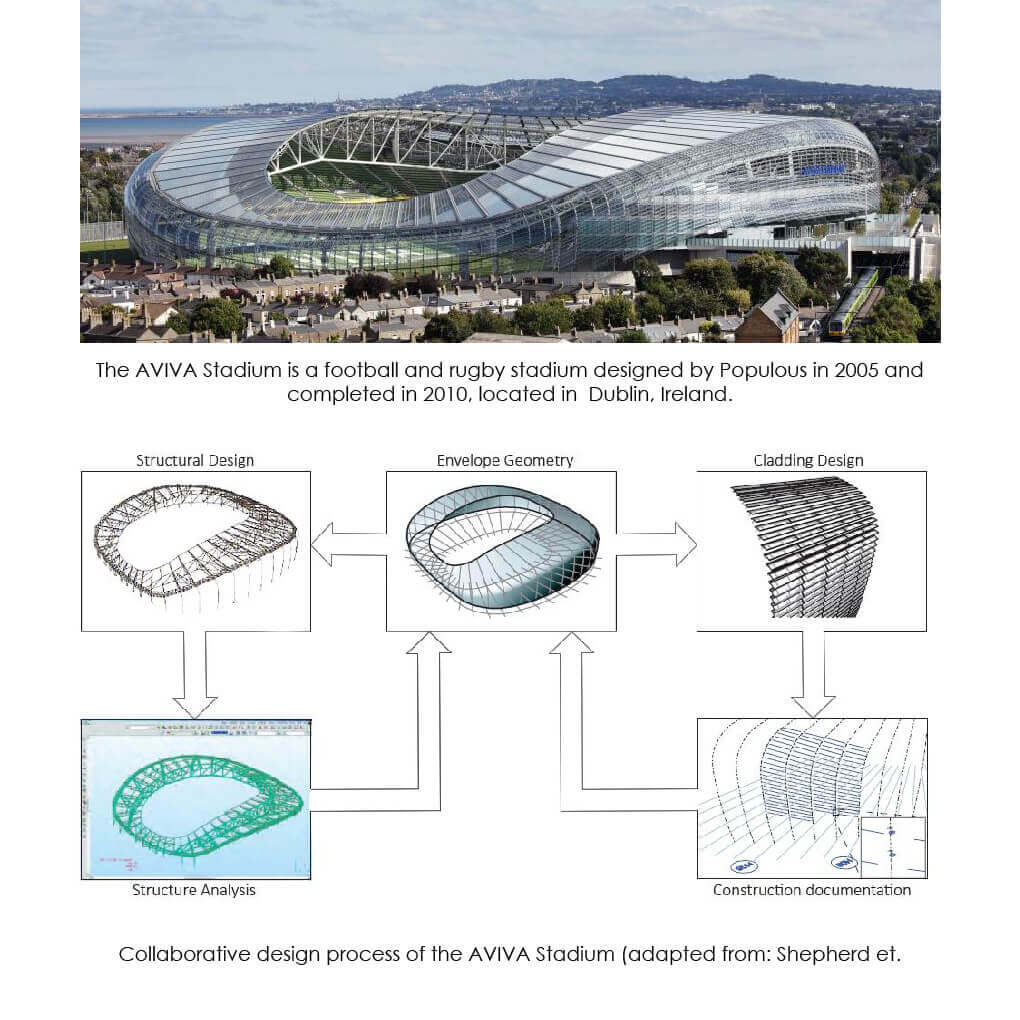

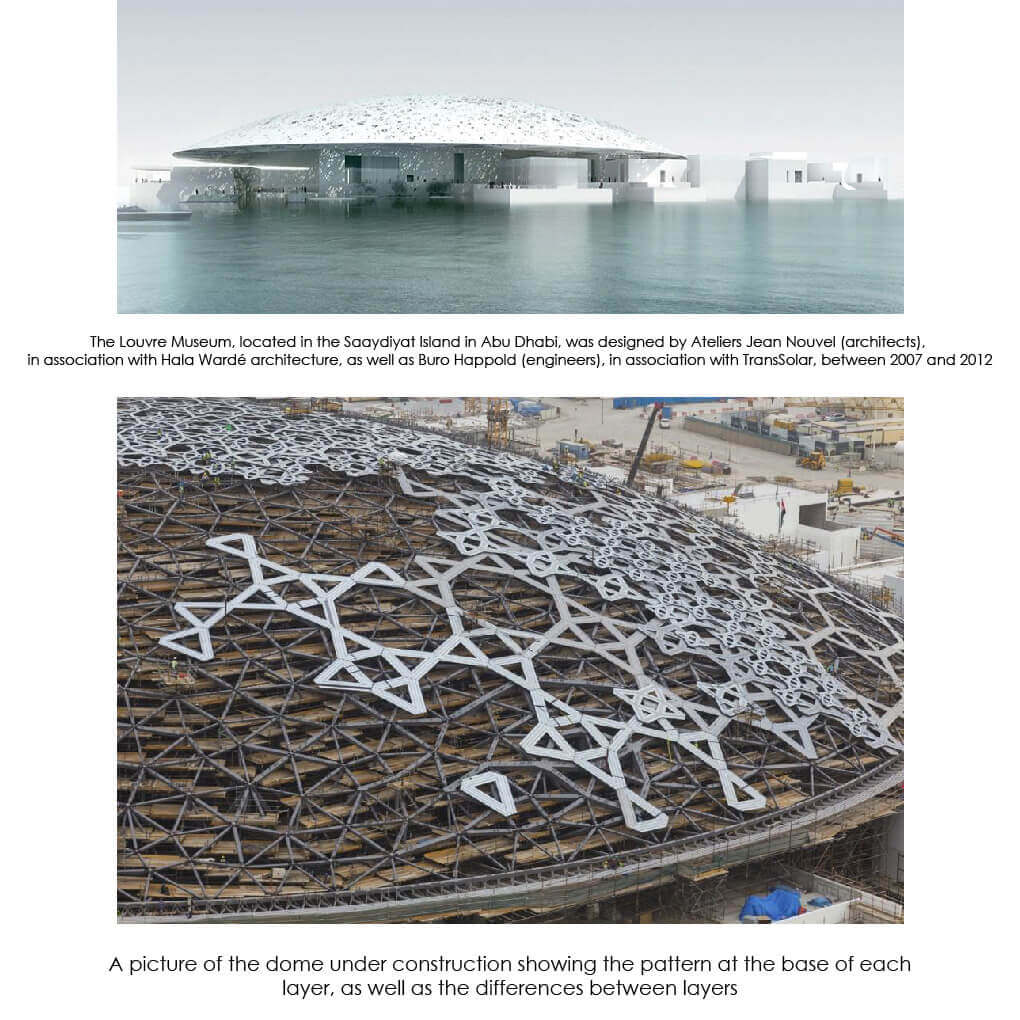

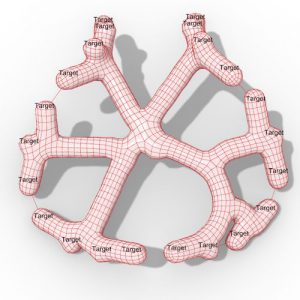

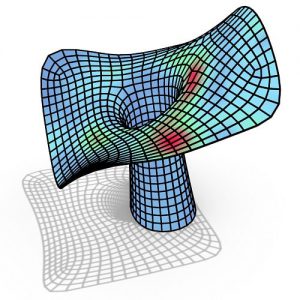

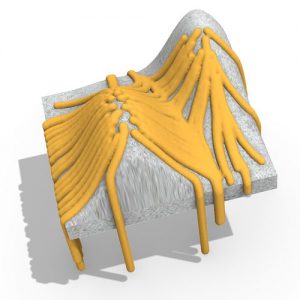

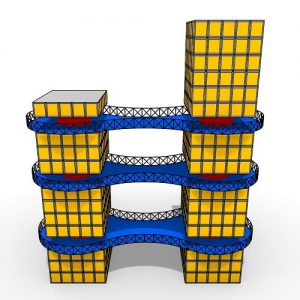

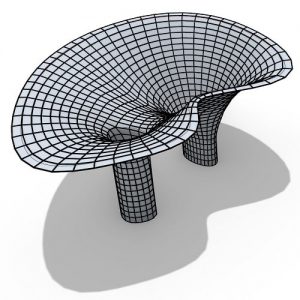

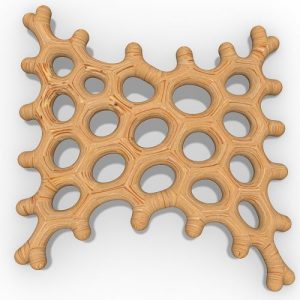

However, where CAD systems proved to have the most appeal for the architectural culture was in their ability to support the design and – in combination with Computer-Aided Manufacturing technologies – construction of buildings with highly complex geometries in a timely and cost-effective manner (Mitchell, 1999), using continuous, digitally-driven design processes. The digitally-enabled, complex, highly curvilinear forms produced from the 1990s onwards (see Figure 1) allowed architects to break away from the norm and experiment with creative and novel forms in architecture (Kolarevic, 2003).

However, where CAD systems proved to have the most appeal for the architectural culture was in their ability to support the design and – in combination with Computer-Aided Manufacturing technologies – construction of buildings with highly complex geometries in a timely and cost-effective manner (Mitchell, 1999), using continuous, digitally-driven design processes. The digitally-enabled, complex, highly curvilinear forms produced from the 1990s onwards (see Figure 1) allowed architects to break away from the norm and experiment with creative and novel forms in architecture (Kolarevic, 2003).

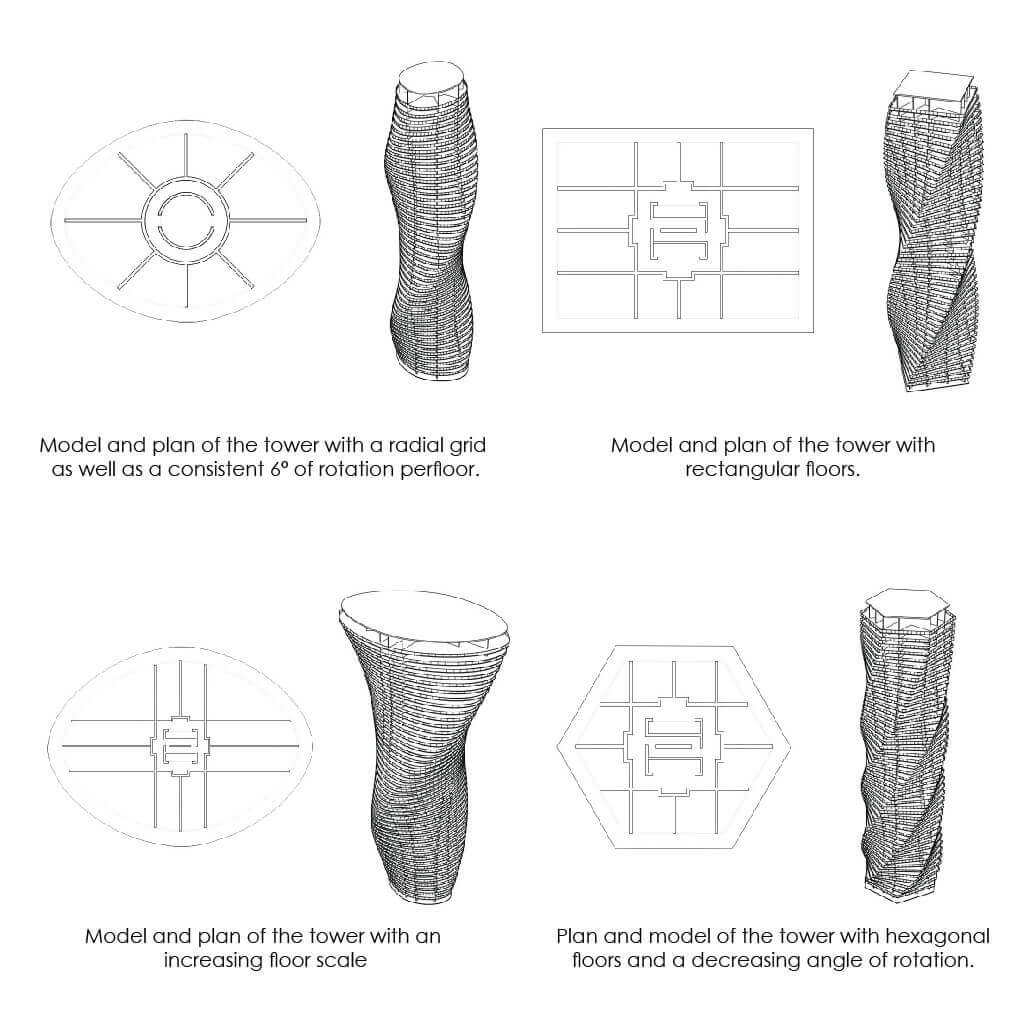

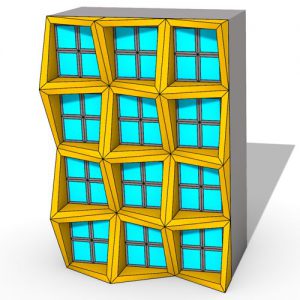

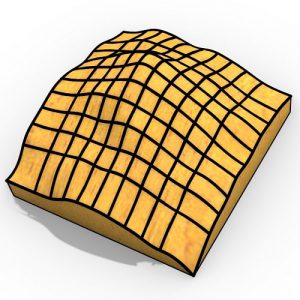

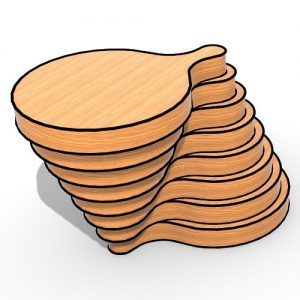

Despite the support provided by CAD systems for the creation of complex geometries, the manual exploration of these geometries can still be a challenging task. The introduction of programming in architecture allowed architects to conceive and efficiently explore complex geometries using algorithmic processes as active agents for form generation in the design process. Algorithmic Design (AD), a programming-based approach to design, uses algorithmic processes to generate forms and shapes.

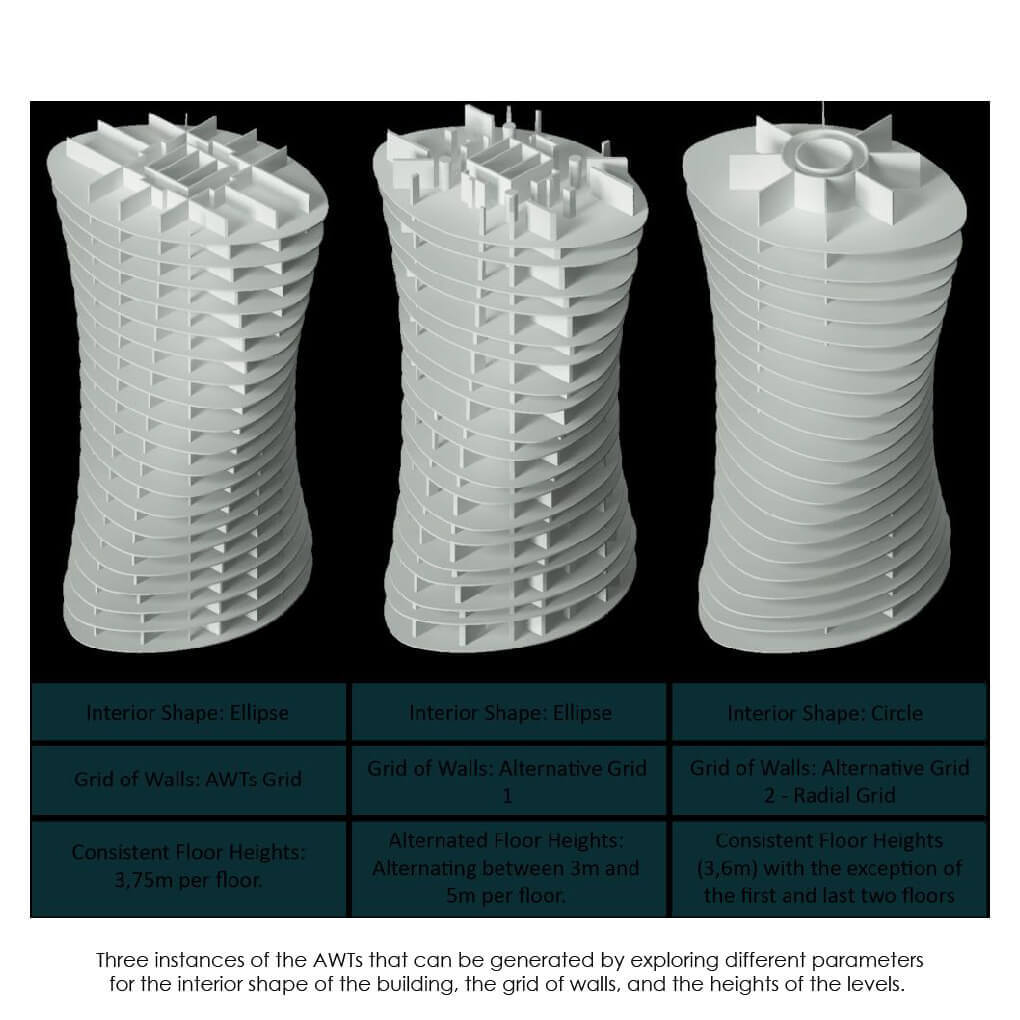

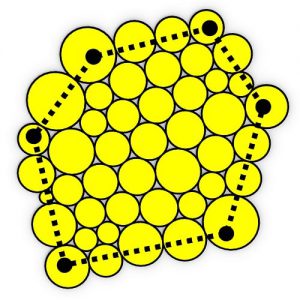

AD introduced a new field of design exploration in architecture, allowing architects to explore a whole domain of “unpredictable” forms, which would have been difficult to explore using manual means (Terzidis, 2003). In addition, because the design generated with AD is typically parameterized, a wide range of different solutions can be quickly generated and tested by providing different values to the parameters, thus supporting exploration and optimization in the design process (Kolarevic, 2003).

AD introduced a new field of design exploration in architecture, allowing architects to explore a whole domain of “unpredictable” forms, which would have been difficult to explore using manual means (Terzidis, 2003). In addition, because the design generated with AD is typically parameterized, a wide range of different solutions can be quickly generated and tested by providing different values to the parameters, thus supporting exploration and optimization in the design process (Kolarevic, 2003).

Finally, AD also brought improvements to architectural design by enabling the automation of repetitive, time-consuming tasks that had to be manually executed before. This relieved architects from tedious and error-prone work, allowing them to save a lot of time and effort during the design process.

Finally, AD also brought improvements to architectural design by enabling the automation of repetitive, time-consuming tasks that had to be manually executed before. This relieved architects from tedious and error-prone work, allowing them to save a lot of time and effort during the design process.

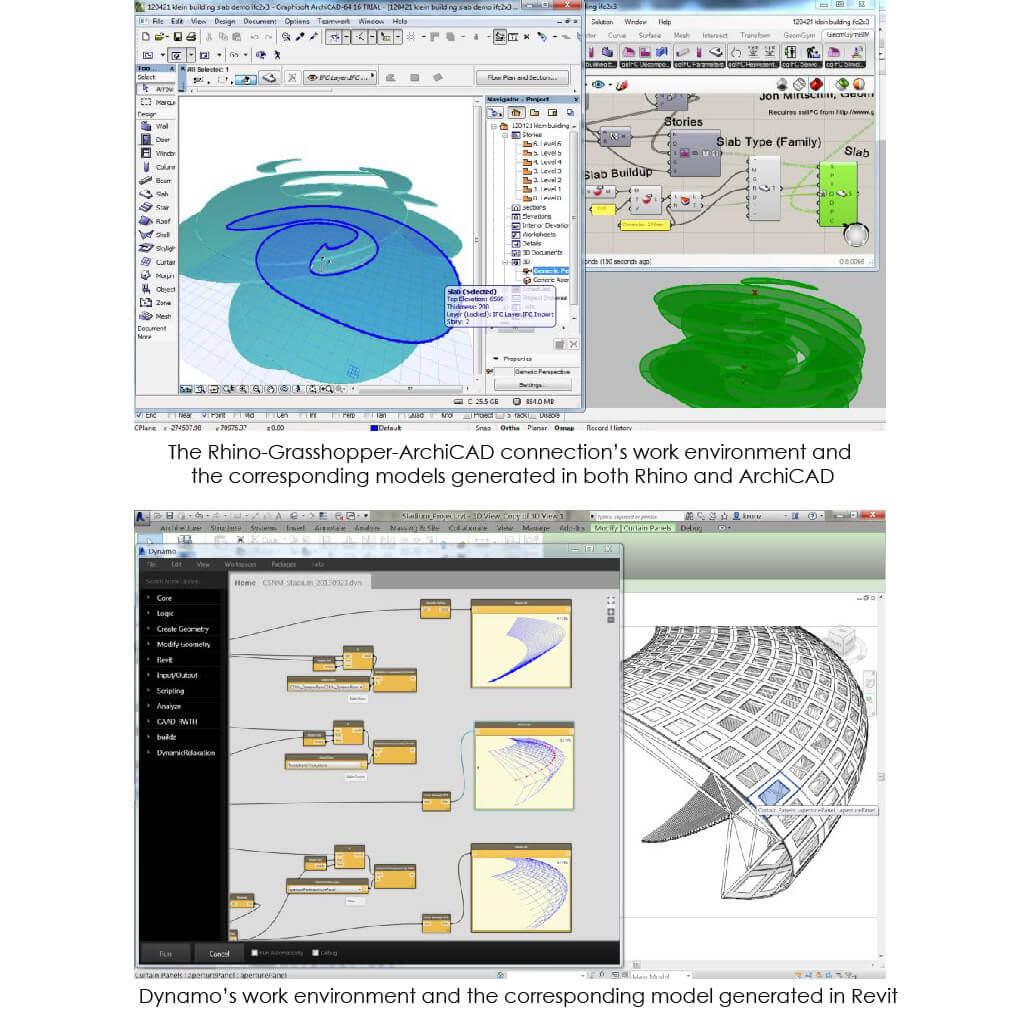

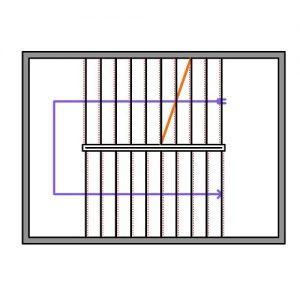

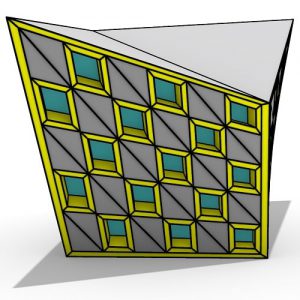

To take advantage of AD, several tools and programming environments were introduced to design softwares commonly used by architects, as is the case of Grasshopper for Rhinoceros 3D, shown in Figure 2, or Visual LISP for AutoCAD. These tools enabled architects with basic programming skills to develop programs that generate models in CAD applications.

To take advantage of AD, several tools and programming environments were introduced to design softwares commonly used by architects, as is the case of Grasshopper for Rhinoceros 3D, shown in Figure 2, or Visual LISP for AutoCAD. These tools enabled architects with basic programming skills to develop programs that generate models in CAD applications.

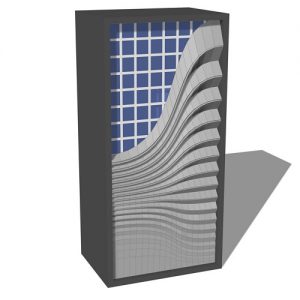

Recently, however, Building Information Modelling (BIM) tools have been re- placing former geometry-based CAD applications in architectural design. CAD and BIM tools are very different, and using the latter involves some significant shifts in design methodologies. For example, while CAD tools mostly deal with geometry, BIM tools produce digital representations of building components, containing both geometrical information and data attributes (Eastman et. al., 2008).

Recently, however, Building Information Modelling (BIM) tools have been re- placing former geometry-based CAD applications in architectural design. CAD and BIM tools are very different, and using the latter involves some significant shifts in design methodologies. For example, while CAD tools mostly deal with geometry, BIM tools produce digital representations of building components, containing both geometrical information and data attributes (Eastman et. al., 2008).

BIM has the potential to bring many improvements to the Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC) industries and, as a result, many major private and government owners all over the world have started to mandate the use of BIM in their projects as a mean to drive the migration to BIM in the building industry (Bernstein et. al., 2014).

BIM has the potential to bring many improvements to the Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC) industries and, as a result, many major private and government owners all over the world have started to mandate the use of BIM in their projects as a mean to drive the migration to BIM in the building industry (Bernstein et. al., 2014).

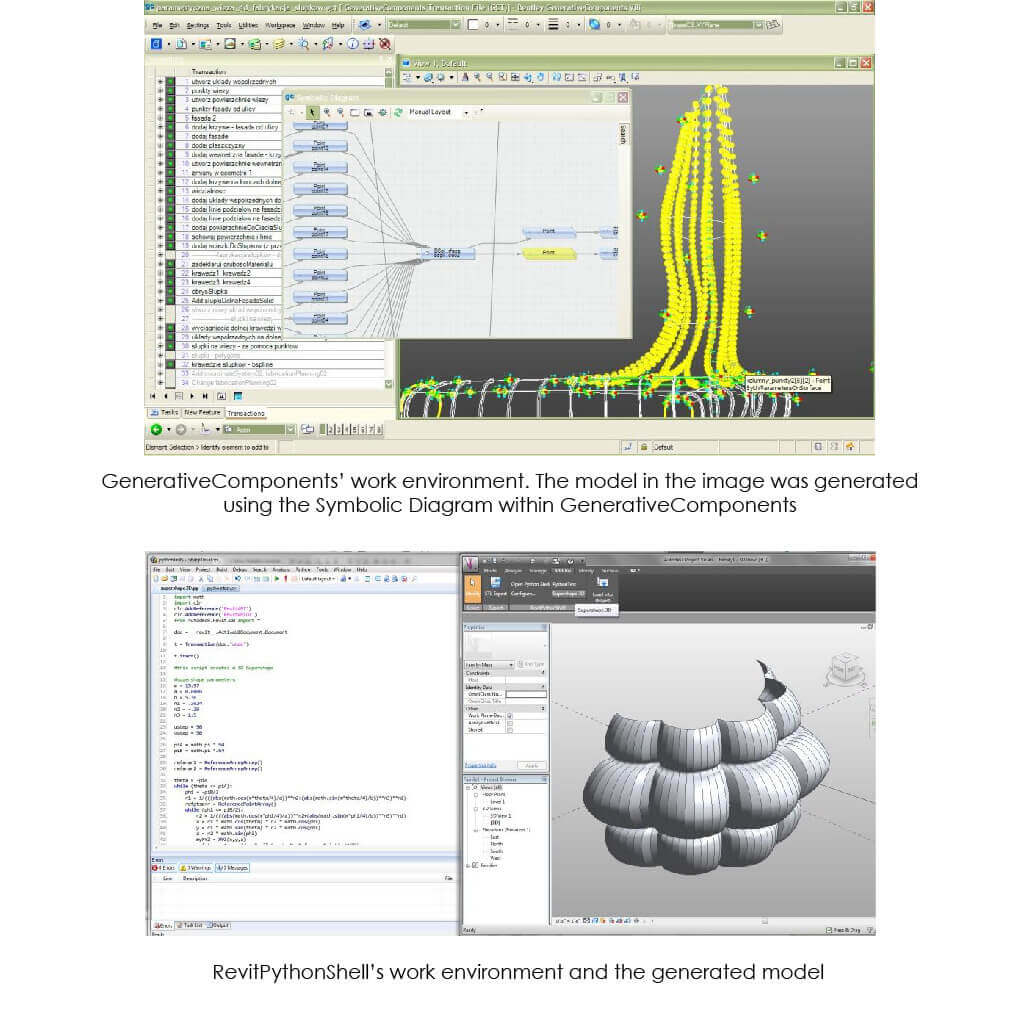

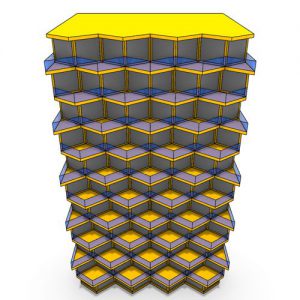

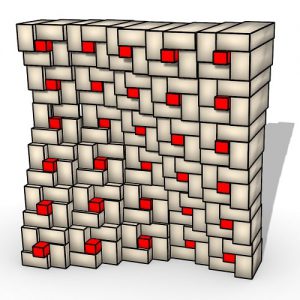

This approach can still benefit from AD and, for that reason, like with former CAD tools, several programming environments and tools have been recently made available to enable the use of AD with BIM applications (Feist et. al., 2016). The result is a new approach to design that combines AD with the BIM methodology and which we designate A-BIM, acronym for Algorithmic-based Building Information Modelling. Although some architects have already started to explore A-BIM in architectural practices over the recent years, this approach has yet to be properly addressed.

This approach can still benefit from AD and, for that reason, like with former CAD tools, several programming environments and tools have been recently made available to enable the use of AD with BIM applications (Feist et. al., 2016). The result is a new approach to design that combines AD with the BIM methodology and which we designate A-BIM, acronym for Algorithmic-based Building Information Modelling. Although some architects have already started to explore A-BIM in architectural practices over the recent years, this approach has yet to be properly addressed.

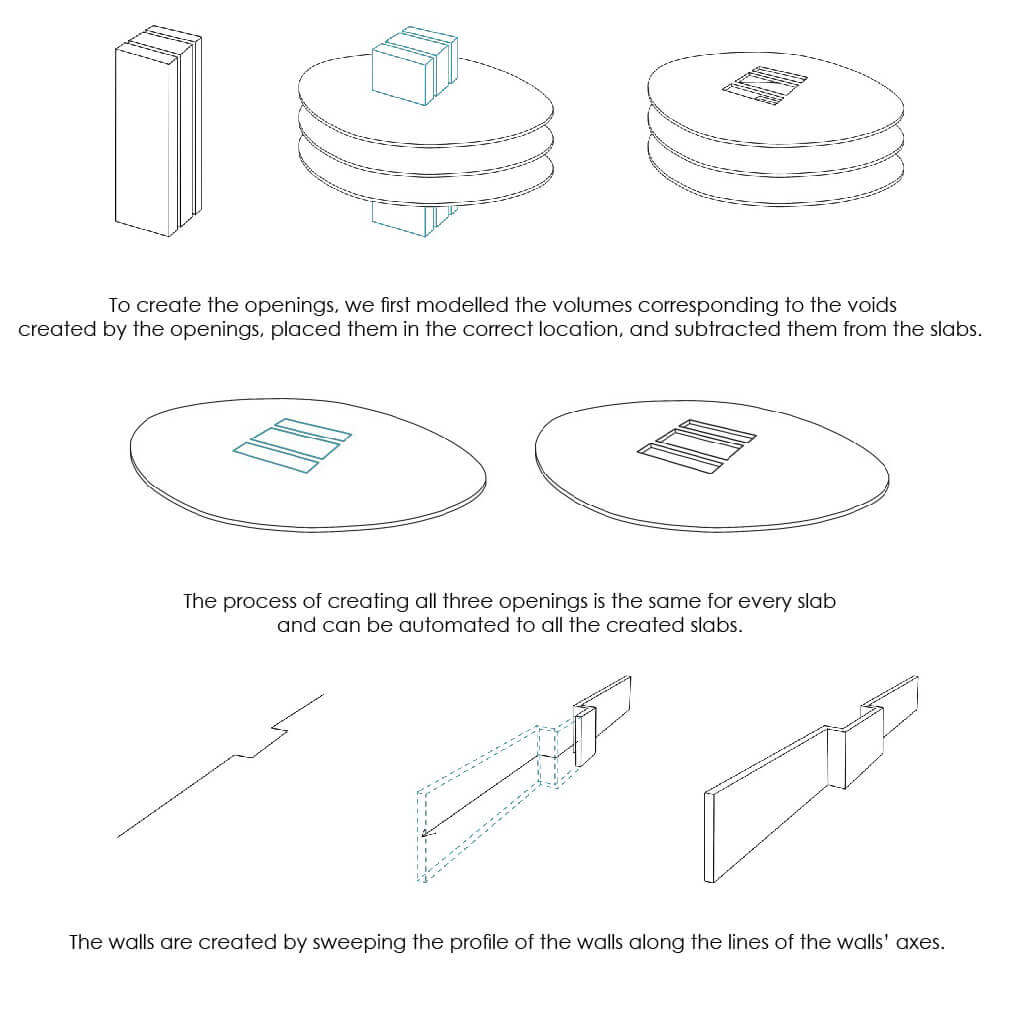

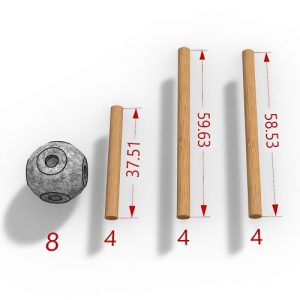

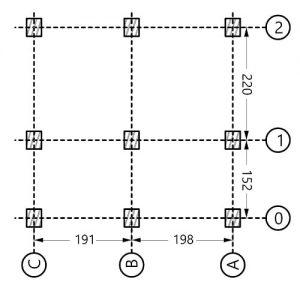

Afterwards, in order to evaluate A-BIM, we selected an architectural case study which we modelled using three different but related approaches: (1) an Algorithmic approach to geometry-based CAD; (2) an Algorithmic-based Building Information Modelling approach with the programming methodology that we propose; and (3) a manual BIM approach. These three approaches are then analyzed and compared in order to find the benefits and drawbacks of A-BIM.

Comments